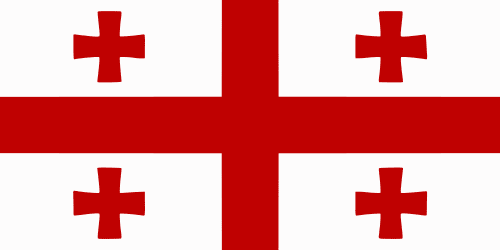

INTRODUCTION OF GEORGIA

Georgia (country), republic in western Asia. Georgia is the westernmost country of the South Caucasus (the southern portion of the region of Caucasus), which occupies the isthmus between the Black and Caspian seas; Azerbaijan and Armenia are also located in the South Caucasus. The name of the republic in Georgian, the official language, is Sakartvelo.

Georgia is a country of extremely diverse terrain, with high mountain ranges and fertile coastal lowlands. Ethnic Georgians constitute a majority of the population. Georgia was made a part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1922. After Georgia gained independence from the USSR in 1991, the country was plagued by civil war and political upheaval. The economy suffered from these events and from severed trading ties with other former Soviet republics, but in the mid-1990s it began to recover when the political strife ebbed and free market reforms were instituted. Georgia’s first post-Soviet constitution was adopted in August 1995.

Georgia includes two autonomous republics: Ajaria, located in Georgia’s southwestern corner, and Abkhazia, in the northwestern arm of the republic. Both republics include stretches of the Black Sea coast. Georgia also contains the autonomous region of South Ossetia, which is located in the north central part of the country. Abkhazia and South Ossetia are bordered on the north by Russia, and Ajaria is bordered on the south by Turkey.

LAND AND RESOURCES OF GEORGIA

Georgia covers an area of about 69,700 sq km (about 26,900 sq mi). It is situated on the east coast of the Black Sea and bounded by Russia on the north and by Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkey on the south. Rugged mountain ranges dominate Georgia’s landscape, constituting about 85 percent of the total land area. The main ridge of the Caucasus Mountains, or Greater Caucasus, forms most of Georgia’s northern border with Russia and contains the country’s highest elevations, including Mount Shkhara (5,200 m/17,060 ft), Georgia’s highest peak. The highest peak fully contained in the country is Mount Kazbek (5,037 m/16,526 ft), in the central Greater Caucasus. Many other peaks reach heights of 4,500 m (15,000 ft) or greater. The Lesser Caucasus mountains occupy the southern part of the republic and rarely exceed an elevation of 3,000 m (10,000 ft). These two mountain systems are linked by the centrally located Surami mountain range, which bisects the country along a northeast-southwest axis. The Surami range includes the Meskheti and Likhi ranges. To the west of this range the relief becomes much lower, and elevations are generally less than 100 m (300 ft) along the river valleys and the coast of the Black Sea. On the eastern side of the Surami Range, a high plateau known as the Kartaliniya Plain extends along the Kura River to the border with Azerbaijan.

The two largest rivers in Georgia, the Kura (Mtkvari) and the Rioni, flow in opposite directions: the Kura, which originates in Turkey, runs generally eastward through Georgia and Azerbaijan into the Caspian Sea, while the Rioni drains into the Black Sea to the west. A delta region known as the Kolkhidskaya Lowlands encompasses the lower Rioni valley as well as most of the Georgian coast. Along with the Rioni, the Inguri and Kodori rivers flow through this fertile region.

Georgia’s climate ranges from year-round subtropical conditions on the Black Sea coast to continental conditions, with cold winters and hot summers, in the extreme east. The mountainous regions have cold, wet winters and cool summers, and the highest peaks are perpetually covered with snow. Annual precipitation also varies by region; along the coast it often exceeds 2,000 mm (80 in), while in the eastern plains it measures between 400 and 700 mm (20 and 30 in).

Georgia contains diverse plant and animal life. Land at lower elevations has been extensively reworked for agricultural purposes and contains little of its native wildlife. The gray marmot, ibex, and chamois, however, can be found in alpine areas, and wolves, foxes, roe deer, and badgers populate the forests. Dense forests and brush cover more than one-third of the country, mostly in the western and mountainous regions. In the eastern uplands, which are sparsely wooded, underbrush and grasses predominate.

Georgia’s natural resources include abundant mineral deposits, such as manganese, iron ore, coal, gold, marble, and alabaster. The republic’s many fast-flowing rivers are an important source of hydroelectricity, and forests provide pulp and timber. Substantial but as yet undeveloped oil deposits are located in the Black Sea shelf near the port cities of Bat’umi and P’ot’i.

Like other republics of the USSR, Georgia suffered severe environmental degradation during the Soviet period, when economic policies emphasizing heavy industry were implemented with little regard for their environmental consequences. As a legacy of these policies, Georgia now suffers from serious pollution. Air pollution is a problem in the major cities, particularly in Rustavi, which has a giant steelworks and other metallurgical industries. In addition, the Kura River and the Black Sea are heavily polluted with industrial waste. As a result of water pollution and the scarcity of water treatment, the incidence of digestive diseases in Georgia is high. The use of pesticides and fertilizers has increased soil toxicity.

Environmental protection did not become a major concern among Georgians until the mid-1980s, but even then systems to control harmful emissions were not readily available. Georgia’s economic problems have hindered the application of recent emission-control technologies. The protection of upland pastures and hill farms from soil erosion is another pressing issue that the government has not addressed owing to lack of economic resources. The government has ratified international environmental agreements pertaining to air pollution, biodiversity, climate change, ozone layer protection, ship pollution, and wetlands.

THE PEOPLE OF GEORGIA

The population of Georgia is 4,615,807 (2009 estimate), giving the country an average population density of 66 persons per sq km (171 per sq mi). Some 51 percent of the country’s inhabitants live in cities. Population is concentrated mainly along the coast of the Black Sea and in river valleys, especially the valley of the Kura River, where Tbilisi, the capital and largest city, is located. The next largest city, K’ut’aisi, is located on the upper Rioni River. Other important urban centers include Bat’umi and Sokhumi, which are the capitals of Ajaria and Abkhazia, and Rustavi, located on the Kura downstream from Tbilisi.

Nearly 100 different ethnic groups make up Georgia’s population. Georgians are the largest group, making up about 70 percent of the population, followed by Armenians (about 8 percent), Russians (about 6 percent), and Azerbaijanis (about 6 percent). Significant numbers of Ossetians, Greeks, and Abkhazians also reside in the republic.

Georgian has been the country’s official language since 1918, when Georgia briefly gained its independence. The language belongs to the South Caucasian, or Kartvelian, language family and uses a distinct alphabet that was developed in the 5th century. A non-Indo-European and non-Turkic language, Georgian is unrelated to any other major world language. Georgian remained the official language of the republic during the Soviet period, although Russian predominated in communications from the central government in Moscow. Georgian is not spoken by many of the country’s ethnic minorities, such as the Ossetians and Abkhazians, who speak their own native languages and frequently Russian as well. Russian is the first language of about 9 percent of the population.

The Georgian identity has been closely tied to religion since the introduction of Christianity in the early 4th century. The Georgian Orthodox Church dates to that time. After about 100 years of subjugation by the Russian Orthodox Church, the Georgian Orthodox Church reclaimed its independence following the Russian Revolution of 1917. During the subsequent Soviet period, religious practice was strongly discouraged because the Soviet state was officially atheistic; however, the Georgian Orthodox Church was allowed to function openly.

Orthodox Christianity is the religion of about 58 percent of the Georgian population. Muslims represent about 19 percent of the country’s population, with ethnic Azerbaijanis, Kurds, and Ajars comprising the principal Muslim groups. Ajars are ethnic Georgians who converted to Islam in the 17th century; they reside primarily in the autonomous republic of Ajaria. Judaism is also practiced, although to a lesser extent.

Georgia has an adult literacy rate of 99.5 percent, a result of the Soviet emphasis on free and universal education. Georgians were among the most highly educated of all the nationalities in the former USSR. Since independence, however, all levels of education in Georgia have been seriously underfunded, resulting in lower educational standards. Most schools are state operated and provide tuition-free education; however, a number of private schools have opened since the early 1990s. Education is compulsory from the first through eleventh grades, and most students enter the school system at age six. Institutions of higher education in Georgia include the University of Tbilisi and Georgian Technical University, both located in Tbilisi. Abkhazia has its own university, Abkhazian State University.

Despite centuries of foreign domination, Georgia has maintained a distinct culture, one influenced by both Asian and European traditions. The Georgian language is one indication of this cultural individuality. Georgia’s ancient culture is evident in the republic’s architecture, which is renowned for the role it played in the development of the Byzantine style. The republic also has a long tradition of highly skilled metalwork, with excavations of ancient tombs revealing finely wrought pieces in bronze, gold, and silver.

Although a Georgian literary tradition dates from the 5th century, the 12th and 13th centuries are considered the golden age of Georgian literary development. The national epic of Georgia, Vepkhis-tqaosani (The Man in the Tiger’s Skin), was written during this period by poet Shotha Rusthaveli (see Georgian Literature). Western European cultural movements, especially romanticism, began to influence Georgian writers and artists during the 19th century. Many Georgian writers produced works of high quality in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Beginning in the 1920s, however, the Soviet regime required artistic works to glorify socialist ideals (see Socialist Realism). Georgian writers and artists were censored and in some cases executed for noncompliance. During the Soviet period, Georgian author Konstantin Gamsakhurdia won acclaim for his historical novels.

The State Literary Museum of Georgia, located in Tbilisi, contains a thorough history of Georgian literature from the 19th and 20th centuries. The State Museum of Georgia, which contains archaeological exhibits, and the Georgian State Art Museum also are located in Tbilisi.

ECONOMY OF GEORGIA

The breakup of the Soviet Union severely dislocated the economy of Georgia by disrupting established trade patterns. Three separate armed conflicts and several years of political instability created even more serious damage. The country’s gross domestic product (GDP), which measures the total value of goods and services produced, declined between 1990 and 1995 by the greatest amount of any former Soviet republic. Georgia became increasingly dependent upon foreign financial and humanitarian aid. But beginning in the mid-1990s, increasing political stability allowed Georgia to make significant progress toward renewing economic growth.

Several attributes brighten Georgia’s long-term economic prospects. The country’s warm climate and position on the eastern shore of the Black Sea make the country suitable for agricultural and tourism development. It also straddles the best transportation routes across the Caucasus Mountains. Abundant rivers flowing from the mountains provide water for crop irrigation and hydroelectric production.

The private sector was active in Georgia even before the end of the Soviet era, with a thriving black market in which everything from bread to cars was bought and bartered illegally. The government adopted a privatization law shortly after independence but delayed its full implementation until the return of political stability in the mid-1990s. While intending to transform state-managed enterprises into profitable companies, the government retains a share of most operations.

Georgia’s GDP in 2007 was $10.18 billion. Agriculture, including forestry and fishing, contributed 11 percent of the total. Industry, including manufacturing, mining, and construction, produced 24 percent of GDP. Services, which include trade and financial activities, accounted for 65 percent. However, a large portion of the Georgian economy is in the so-called informal sector and outside of usual economic reporting.

Agriculture is an important feature of the Georgian economy, and the country has one of the most diverse agricultural sectors of any of the former Soviet republics. The lowlands of the west have a subtropical climate and produce tea and citrus fruits, while grapes and deciduous fruits grow in the uplands. The country’s long growing season allows it to grow almost any crop, and Georgia also produces large amounts of vegetables and grains. Draining of swampy coastal lowlands around the mouth of the Rioni River added much fertile land. Livestock raising is also important; milk from cows and goats is used to make cheese. The agricultural sector provides 54 percent of employment.

The processing of agricultural goods is the most significant part of Georgia’s industrial activity. The country also gained importance as an industrial region because of the abundance of mineral deposits (manganese, iron ore, molybdenum, and gold) and fuel (coal and petroleum). The industrial sector provided 9 percent of employment in 2005.

During the Soviet period the Georgian Black Sea coast was a favorite vacation area for residents of the Soviet bloc. Visitation to the resorts nearly ceased in the early 1990s with the outbreak of armed conflict and economic disintegration. With the return of political stability, the region regained its potential as a tourist destination.

Energy shortages hampered the Georgian economy beginning in 1993, when prices for imported fuels from Russia and other suppliers increased. The government of Georgia rationed household electricity and heating fuel during winters, power outages were frequent and long lasting, and many industries were closed due to fuel shortages. Energy shortages were subsequently eased through the development of the country’s capacity for hydroelectric power. In 2006 hydroelectricity accounted for 74 percent of the country’s total power generation.

Meanwhile, Georgia’s improving economy increased its ability to pay for fuel imports. In addition, Georgia leveraged its strategic location to bargain for its interests in the construction of new oil and natural gas pipelines through its territory. The first of these, a petroleum pipeline from Baku, Azerbaijan, to Supsa on Georgia’s Black Sea coast, opened in 1999. Two additional pipelines, transporting both petroleum and natural gas from the Caspian fields of Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey, commenced operations in 2005 and 2006. Georgia receives a portion of the transported fuel as a transit fee.

During the Soviet period nearly all of Georgia’s trade was with other republics of the former Soviet Union. Following independence Georgia worked to establish new trading relationships. Turkey became its principal trading partner, accounting for more than a quarter of total trade. Leading exports are metal products, coffee, tea, and beverages; chief imports are energy and food products.

Aided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the government reduced inflation from 62 percent per month in 1994 to less than 1 percent per month in 1997. In September 1995 the Georgian government introduced a new currency, the lari, in an attempt to stabilize the economy and improve living conditions (1.70 lari equal U.S.$1; 2007). The lari replaced the Georgian coupon, a provisional currency that had declined dramatically in value since being issued in July 1993.

GOVERNMENT OF GEORGIA

Georgia is a democratic republic with a strong executive presidency. In August 1995 a new constitution replaced the 1992 decree on state power, which had been instituted as an interim constitution after Georgia declared its independence. The new constitution reestablished the presidency, which had been created in 1991 but was abolished after the country’s first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, was ousted in 1992. According to the 1995 constitution, the president, who is head of state, is directly elected to a maximum of two five-year terms. The new constitution abolished the post of prime minister, but a constitutional amendment adopted in February 2004 reintroduced the position. The prime minister heads the government, whose ministers oversee the day-to-day functions of government in their jurisdictions. They are ultimately accountable to the president. All citizens aged 18 and older may vote in Georgia.

The 1995 constitution also established a new unicameral (single-chamber) legislature called Parliament. All 235 members of Parliament are elected to four-year terms, with 150 elected on a proportional basis (with the number of delegates from each party corresponding to the proportion of the total vote that party receives) and 85 elected by majority vote in single-member constituencies (one elected delegate per territorial unit). The new legislature replaced the State Council, which had been created in October 1992; between 1992 and 1995 the chairperson of the State Council had held executive powers in place of a president.

Each of Georgia’s autonomous political entities—the republics of Ajaria and Abkhazia and the region of South Ossetia—has its own locally elected government, consisting of a legislature and a local leader. The local governments of Abkhazia and South Ossetia are not recognized by the central government, however, because of the long-standing secessionist conflicts in these regions. Abkhazia is essentially independent, and South Ossetia is almost independent. Ajaria does not seek secession from Georgia; its local government cooperates with the central government and recognizes the constitution of Georgia as the guiding force for local legislation. For purposes of local administration, the remainder of Georgia is divided into prefectures headed by prefects appointed by the Georgian president, who report to the central government.

Georgia’s judiciary is based on a civil-law system. The Supreme Court is the highest court. Its judges are elected by the legislature, on the recommendation of the president, for a term of ten years. Georgia also has a Constitutional Court, which rules on the constitutionality of new legislation. The president, the legislature, and the Supreme Court each appoint three of the nine judges of the Constitutional Court, who serve for ten years.

During the Soviet period, Georgia had no armed forces separate from the centrally controlled Soviet security system. After the republic declared its independence in 1991, the Georgian government set a high priority on developing a unified national military. Georgia’s defense forces now include an army of 7,042 troops (with plans to increase the army to 20,000), a navy of 1,350, and an air force of 1,350. All males must begin a two-year period of military service when they reach the age of 18.

Georgia was admitted to the United Nations (UN) in July 1992. In 1993 Georgia became a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a loose political alliance of most of the former Soviet republics. In 1994 the republic joined the Partnership for Peace program, which provides for limited military cooperation with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Georgia is also a member of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

HISTORY OF GEORGIA

Origins

In about the 500s BC, western Georgia was colonized by Ionian Greeks; its western part was known as Colchis and the eastern region as Iberia. Christianity was introduced in the early 4th century AD. The Persian and Byzantine empires then fought for control over Georgia until the 7th century, when the region was conquered by the Arabs.

In the 11th century King Bagrat III united the Georgian principalities into one kingdom, with the exception of Tbilisi, which was an emirate (territory ruled by an emir, or Turkish prince) under the control of Seljuk Turks. In 1122 King David II, one of Bagrat’s descendants, expelled the Turks and recovered Tbilisi. Under Queen Tamar, whose rule straddled the 12th and 13th centuries, the Georgian kingdom reached its zenith and grew to include most of the Caucasus. Georgian culture also experienced a golden age during this period. Then in the 13th century, Mongol armies invaded the Georgian lands. By the end of the 15th century the Georgian kingdom had disintegrated entirely as a result of the Mongol invasions.

Iranian and Ottoman Empires

In the early 1500s the Iranian and Ottoman empires invaded Georgia. In 1553 the two Muslim powers partitioned Georgia’s territory, with Iran taking the east and the Ottomans taking the west. The Iranians and the Ottomans fought against one another for complete control of Georgia until the late 1500s, when the Ottomans were driven out. In the 1720s the Ottomans attempted another conquest, but the Iranians expelled them again. Iran then placed the Georgian kingdom of Kartli under the rule of local Bagratid royals. The Bagratids had originated in the borderlands between Georgia and Armenia. Originally an Armenian dynasty, one branch of the Bagratids eventually became Georgianized.

Kingdom of Georgia

In 1762 Erekle II of the Bagratids reunited the eastern Georgian regions of Kartli and Kakheti, forming a new Georgian kingdom that covered much of present-day Georgia. In the late 1700s King Erekle turned to Russia for protection against foreign conquest, primarily by Iran, and in 1783 he accepted Russian suzerainty in return for Russia’s guarantee to maintain his kingdom’s borders. Nevertheless, Iranian forces sacked Tbilisi in 1795. In 1801 Russia deposed the Bagratid king and annexed the eastern Georgian kingdom to the Russian Empire. Russia annexed the western Georgian region of Imereti in 1810 and the remainder of western Georgia between 1829 and 1878.

The Soviet Period

The Russian Empire collapsed in the Russian Revolution of 1917, and an independent Georgian state was established in May 1918. The Mensheviks, or moderate socialists, initially controlled the Georgian government. However, in 1921 during the Russian Civil War, Red Army troops invaded the country under the orders of Bolshevik (militant socialist) officials Joseph Stalin and Grigory Ordzhonikidze, both native Georgians. In ordering the invasion, Stalin and Ordzhonikidze were acting against the wishes of Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin. See also Bolshevism.

Georgia was now under the control of the Bolsheviks (later known as the Communists). Stalin was, at the time, directing nationality affairs from the central government in Moscow. From this position, he hatched a scheme to join Georgia with Armenia and Azerbaijan. This union was to form a new political entity, the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (SFSR). In December 1922, when the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was founded with four constituent republics, one of them was the Transcaucasian SFSR. However, in 1936 the Transcaucasian republic was dissolved, and Georgia became its own constituent Soviet republic, as did Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Georgian republic was called the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR).

Meanwhile, in July 1921 the Ajarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) was formed within Georgia. Abkhazia was initially a separate Soviet republic, but in 1921 it was merged with Georgia, and in 1931 it was downgraded to the status of an autonomous republic. In April 1922 the Soviet government created the political entity of South Ossetia and designated it an autonomous region within Georgia, while its northern counterpart on the other side of the Greater Caucasus, North Ossetia (now Alania), became part of Russia.

Georgians vigorously resisted Soviet rule, but by 1924, many Georgian dissidents had been executed and others imprisoned on the orders of the central government in Moscow. Even active nationalists who were members of the Communist Party of Georgia, the only political party allowed to function, were punished in an attempt to wipe out all nationalist tendencies in the republic. In the late 1920s Stalin established himself as the undisputed leader of the Soviet Union, ushering in a despotic regime that lasted until his death in 1953. Stalin’s close associate Lavrenty Beria served as first secretary of the Communist Party of Transcaucasia, and then of the Communist Party of Georgia, throughout the 1930s. During the Great Purge (1936-1938)—a campaign of terror that served to solidify Stalin’s dictatorship—Beria collaborated with Stalin to carry out massive arrests and executions of Georgian party officials, intellectuals, and rank-and-file citizens.

During World War II (1939-1945), Stalin ordered the deportation of entire minority groups, mainly Turkic, from Georgia and the rest of the Caucasus on the assumption that they would support the invading Axis powers. After Stalin’s death, a liberalizing process known as de-Stalinization was implemented throughout the Soviet Union under Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.

In 1972 Eduard Shevardnadze was appointed first secretary of the Communist Party of Georgia, a post he held until his promotion to head of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1985. In the 1980s Shevardnadze became an outspoken supporter of the reformist policies of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

However, Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost (Russian for “openness”) and perestroika (“restructuring”), introduced in the mid-1980s, led many Abkhazians and Ossetians in Georgia to begin agitating for increased autonomy. Friction between the Georgian government and these ethnic minorities increased after the Georgian Supreme Soviet (legislature) passed a law establishing the Georgian language as the official state language in 1989. On April 9 of that year, demonstrators in Tbilisi, who were demanding that Abkhazia remain a part of Georgia and advocating Georgian independence from the USSR, were attacked by Soviet security forces. Nineteen people were killed and many others injured, resulting in increased anti-Soviet sentiment.

Georgian Independence

In the late 1980s Communist regimes collapsed in many nations of Eastern Europe, strengthening the independence movements already stirring in the Soviet republics. For the first time during the Soviet period, political parties other than the Communist Party were allowed to participate in elections to the Georgian Supreme Soviet, held in November 1990. The Communist Party of Georgia lost its monopoly on power, with the majority of votes going to the Round Table-Free Georgia coalition of pro-independence parties. Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the leader of the coalition and a longtime nationalist dissident, became chairperson of the new legislature and Georgia’s de facto head of state. In April 1991 the Georgian Supreme Soviet declared the republic’s independence from the USSR. In August the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) collapsed after conservative Communists botched a coup attempt against Gorbachev, and in December the USSR officially collapsed.

In May 1991 Gamsakhurdia was elected as Georgia’s first president. Serious internal strife developed soon afterwards, and in September and October a number of opposition parties charged Gamsakhurdia with imposing an authoritarian style of leadership and staged a series of demonstrations demanding his resignation. Gamsakhurdia responded by ordering the arrest of opposition leaders and declaring a state of emergency in Tbilisi. In December armed conflict broke out in the capital, and opposition forces besieged Gamsakhurdia in the government’s headquarters. Gamsakhurdia and some of his supporters fled the capital in early January 1992, and the opposition declared him deposed. Georgia’s presidency was abolished, and former Soviet official Shevardnadze was chosen in March to lead the country as acting chairperson of the State Council (the country’s new legislature). Shevardnadze was elected to the post by popular vote later that year. Gamsakhurdia’s followers made several attempts to reinstate him by force, but these attempts were not successful, and Gamsakhurdia died in late 1993 or early 1994 in circumstances that never have been fully clarified.

Following independence, Georgia’s Ossetian and Abkhazian minorities continued to seek greater levels of autonomy for their regions but were faced with increasing nationalist sentiment among the Georgian majority. Violent fighting between Ossetians and Georgians had begun in 1989, and this fighting continued in South Ossetia until a peacekeeping force of mostly Russian troops was deployed in 1992. Then in July of that year, the leaders of Abkhazia declared the independence of their republic. Georgian authorities sent troops into Abkhazia, and heavy fighting broke out in the region. By October 1993 Abkhazian forces had expelled the Georgian militia and more than 200,000 ethnic Georgians had fled from Abkhazia. In the same month the Georgian government joined the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in order to win Russian military support. In February 1994 Russia and Georgia reached an agreement that allowed Russia to maintain three military bases on Georgian territory in exchange for military training and supplies.

In April 1994 a UN-sponsored agreement was reached that established an immediate cease-fire in Abkhazia, to be guaranteed by a force of about 2,500 Russian peacekeeping troops. The agreement also established committees to oversee the repatriation of Georgians who had fled the area. By the end of the year, about 30,000 refugees were reported to have returned to their homes in the region. Under the agreement, Abkhazia was to remain part of Georgia while maintaining a high degree of autonomy. When Abkhazia adopted its own constitution in November, however, it declared itself an independent state. In February 1995 the Abkhazian leadership announced that the republic was abandoning its demands for complete secession from Georgia and would instead insist upon a confederal structure of two sovereign states.

New Constitution

In August 1995 the Georgian legislature approved a new constitution, which restored the office of the presidency and established a 235-member legislature. The constitution did not define the territorial status of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

In November, presidential and legislative elections took place in Georgia. The elections were not held in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, where sporadic clashes continued to occur. Shevardnadze was overwhelmingly elected as president, winning more than 70 percent of the vote. His party, the Citizens’ Union of Georgia, won the largest number of seats in the new legislature.

In January 1996 CIS leaders agreed, at Shevardnadze’s request, to impose economic sanctions against Abkhazia until it agreed to rejoin Georgia. In November 1996 both Abkhazia and South Ossetia held local elections that the Georgian government declared invalid. By the end of the year, however, the governments of Georgia and South Ossetia reached an agreement to avoid the use of force against one another, and Georgia pledged not to impose sanctions against South Ossetia. In early 1997 more Georgian refugees were reportedly repatriated to Abkhazia. More than 30,000 people fled their homes in Abkhazia in May 1998 because of renewed fighting between separatist and pro-Georgian forces. A political settlement regarding the territorial status of the two regions remained out of reach, and Russian troops continued to maintain a peacekeeping presence.

In February 1998 President Shevardnadze survived an assassination attempt when his motorcade was attacked in Tbilisi by a group of men armed with guns and grenade launchers. The president had survived another attempt on his life in 1995. Four or five Gamsakhurdia supporters were arrested in February, but Shevardnadze accused reactionary forces in Russia of masterminding and participating in the attack. In October 1998 Gamsakhurdia supporters in the military led a one-day revolt, taking over the army garrison at Senaki, then marching on K’ut’aisi. The mutinous soldiers fought with government troops, but surrendered after talks with government negotiators.

In legislative elections held in October 1999, the Citizens’ Union of Georgia won a majority of the seats. Shevardnadze was reelected president in April 2000, although election monitors criticized the election as flawed and Shevardnadze faced a declining economy.

Political Upheaval

Economic ills and charges of government corruption caught up with Shevardnadze in November 2003 when he was forced to resign. Parliamentary elections on November 2 were reportedly marred by fraud. Both the United States and international election monitors from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) denounced the election, citing ballot-box stuffing and other voting irregularities. Tens of thousands of opposition supporters demonstrated for weeks to protest the election results. Then, in late November, the protesters seized the Parliament building and forced Shevardnadze to vacate his office. When the military failed to come to his defense, Shevardnadze resigned. Opposition leader Mikhail Saakashvili proclaimed a “velvet revolution,” similar to the nonviolent uprising that ousted the Communist government of Czechoslovakia in 1989. Georgia’s nonviolent coup became known as the Rose Revolution for the rose that Saakashvili carried in his mouth as he entered the Parliament building during the takeover.

As required by Georgia’s constitution, the parliamentary speaker, Nino Burdzhanadze, an opposition leader and former member of Shevardnadze’s inner circle, became acting president. Saakashvili was elected president by an overwhelming margin in January 2004. The following month the Parliament of Georgia adopted several constitutional amendments, which among other provisions created the post of prime minister to head the government.

Soon after the revolution, President Saakashvili was faced with a growing crisis in the autonomous region of Ajaria, whose long-standing president, Aslan Abashidze, refused to recognize Saakashvili’s full authority as president of Georgia. In early May 2004 Abashidze claimed that government forces were preparing to invade Ajaria and ordered his forces to blow up bridges and dismantle railway lines connecting Ajaria with the rest of Georgia. Saakashvili threatened Abashidze with forced removal if he refused to disarm his forces and comply with the constitution of Georgia. Faced with eroding support, including large pro-Saakashvili demonstrations in Bat’umi, Abashidze resigned and left the country.

New parliamentary elections were held in March 2004 to fill the 150 seats in the 235-seat Parliament chosen by proportional representation. The November 2003 election results for these seats had been annulled, but the results for the remaining 85 seats, chosen by majority vote in single-member constituencies, had been deemed valid. A pro-Saakashvili coalition of the National Movement and the United Democrats won 135 seats, giving it a total of 152, and an opposition alliance called the Rightist Opposition (formed by the Industrialists and the New Rights Party) won 15 seats, bringing its total to 23.

In late 2007 Saakashvili faced a political crisis as massive demonstrations erupted in Tbilisi calling for his resignation and early presidential elections. Opposition protesters accused Saakashvili of corruption and authoritarianism. On the sixth day of protests riot police used force—including tear gas, water cannons, and rubber bullets—to disperse the protesters. Saakashvili called a nationwide state of emergency, which was subsequently approved by Parliament. He acceded to the opposition demand for early elections, announcing they would be held in January 2008, and the state of emergency was lifted after nine days, on November 16. Saakashvili won the January 2008 presidential election with nearly 52 percent of the vote and appeared to cement his control when his party, the renamed United National Movement, won about 60 percent of the vote in the May 2008 parliamentary elections.

International Crisis

Perhaps emboldened by his election victories, his success in Ajaria, and his increasingly closer relations with the United States and the European Union (EU), Saakashvili sent a large military force into South Ossetia in early August 2008. The move reportedly came only hours after the Georgian government and South Ossetian separatist forces had agreed to hold talks mediated by Russia, according to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). The surprise attack included an artillery barrage on the South Ossetian capital of Ts’khinvali, where a Russian peacekeeping force was based. The barrage killed a number of civilians.

In response to the attack, Russia sent an invasion force into South Ossetia. The fighting resulted in hundreds of casualties on both sides, and thousands of people, both Georgian and Ossetian, became refugees as they tried to escape the war zone. In attacking Georgian troops, Russian forces advanced beyond South Ossetia, going as far as the city of Gori and the Black Sea port of Poti, where Russian troops sank a number of Georgian naval vessels.

The United States and the EU immediately condemned the Russian invasion as a violation of Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. French president Nicolas Sarkozy, acting as the EU president, tried to arrange a ceasefire. After a week of fighting, which also spread to parts of Abkhazia, a ceasefire was agreed to and Russian forces began withdrawing from so-called buffer zones in Georgia just outside South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Under the terms of the ceasefire, the Russian withdrawal was completed by mid-October, and civilian EU monitors took up stations in the buffer zones to ensure compliance with the ceasefire.

In late August, Russia’s parliament passed a resolution recognizing the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russian president Dmitri A. Medvedev backed the Russian parliament’s action. In a statement recognizing the independence of the two regions, Medvedev argued that the people of both regions had expressed their desire for independence in several referenda. Saakashvili accused Russia of attempting to annex the two areas, and he pulled Georgia out of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Russia appeared to be isolated in its position, as no other major power was expected to extend recognition. Significantly, Russia failed in an effort in late August to get an endorsement for its actions from the Shanghai Cooperation Council, a regional alliance that includes China and the Central Asian nations of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The United States sent aid to Georgia using a Coast Guard ship that docked at the Black Sea port of Bat’umi, and U.S. secretary of state Condoleezza Rice said the United States might increase military aid to Georgia, which already included U.S. military advisers. But several political observers said the conflict would probably end any possibility of Georgia joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in the near future. In April 2008 the administration of U.S. president George W. Bush had asked NATO to begin the process of admitting Georgia as a member, known as a Membership Action Plan, but France and Germany blocked the request. Under the terms of the NATO pact, any nation with an ongoing border dispute cannot be admitted as a member. With South Ossetia and Abkhazia demanding secession, Georgia’s application for membership would likely be disqualified. Russia vehemently opposes Georgia’s attempt to join NATO and accuses the United States of attempting to encircle it with NATO-bloc countries.

Although Russia had complied with the terms of the ceasefire by the October deadline, Georgian officials continued to demand that Russian forces withdraw from the Kodori Gorge region in Abkhazia and from the Akhalgori district in South Ossetia. Georgia had administered these regions prior to the August war. Georgia also demanded that ethnic Georgians be allowed to return to their homes in the disputed territories and that EU monitors be given access to both Abkhazia and South Ossetia, not just the buffer zones outside them.